How Similar are the Number & Counting Systems in Chinese and Japanese?

How similar are Chinese and Japanese numbers? If you learn to count in one language, does it make the other one easier to learn?

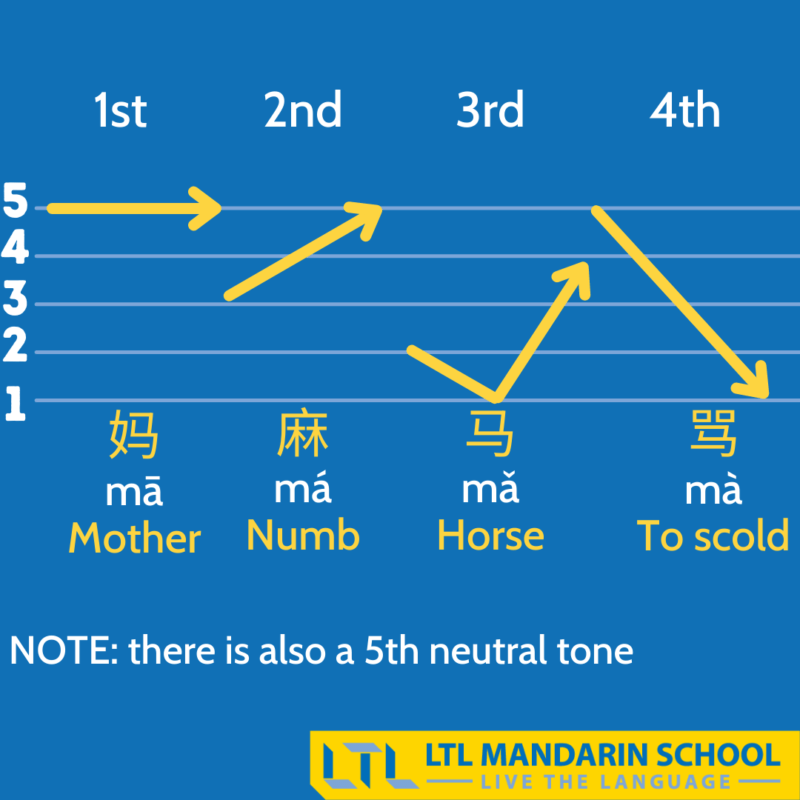

Chinese and Japanese are vastly different in many aspects, particularly grammar and pronunciation (Chinese has tones, Japanese does not), not to mention Japanese has three writing systems, whereas Chinese only has one.

However, a large part of the Japanese writing system, the characters known as Kanji, originated from the Chinese language.

This means there is a surprising amount of crossover in Chinese and Japanese written languages!

In this article, we’ll give you an introductory overview of the similarities and differences between Chinese and Japanese counting systems.

If you would like to learn about each language in greater detail, check out our Japanese Number Guide and Chinese Number Guide!

Note: in this article, when we refer to Chinese, we’re talking about Mandarin Chinese used in mainland China. However, for those keen beans out there we also have courses available for Cantonese, Shanghainese and Hokkien!

Chinese and Japanese Numbers || Reading and Writing 1-10,000

Chinese and Japanese Numbers || How to Say the Date

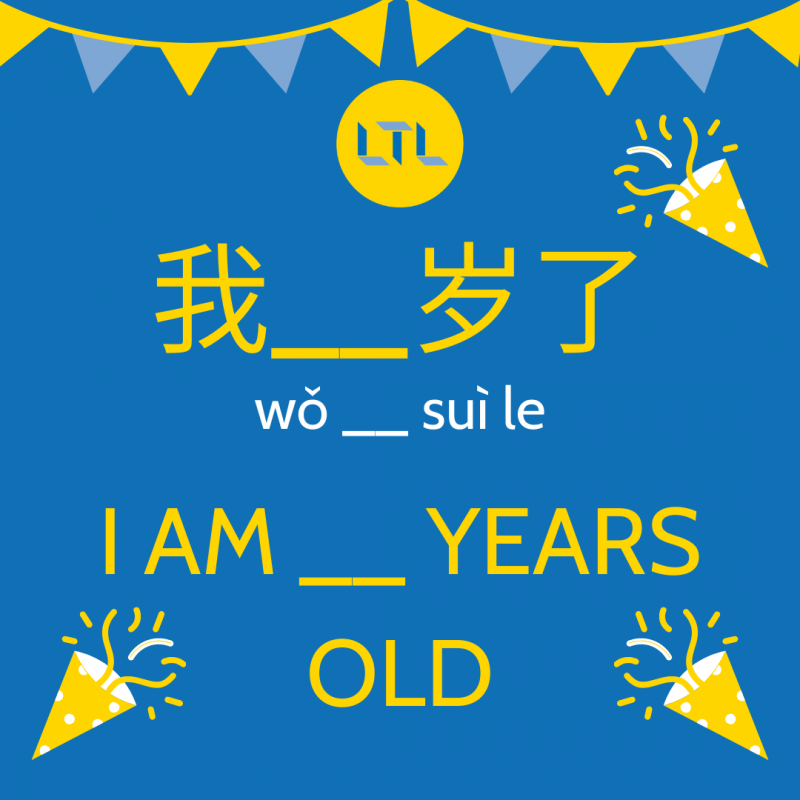

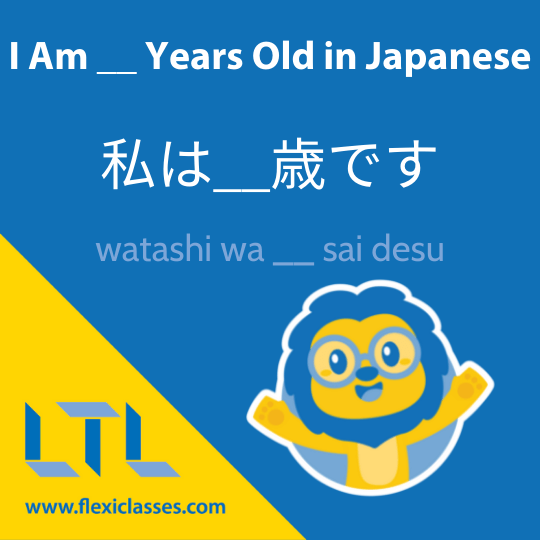

Chinese and Japanese Numbers || Ages

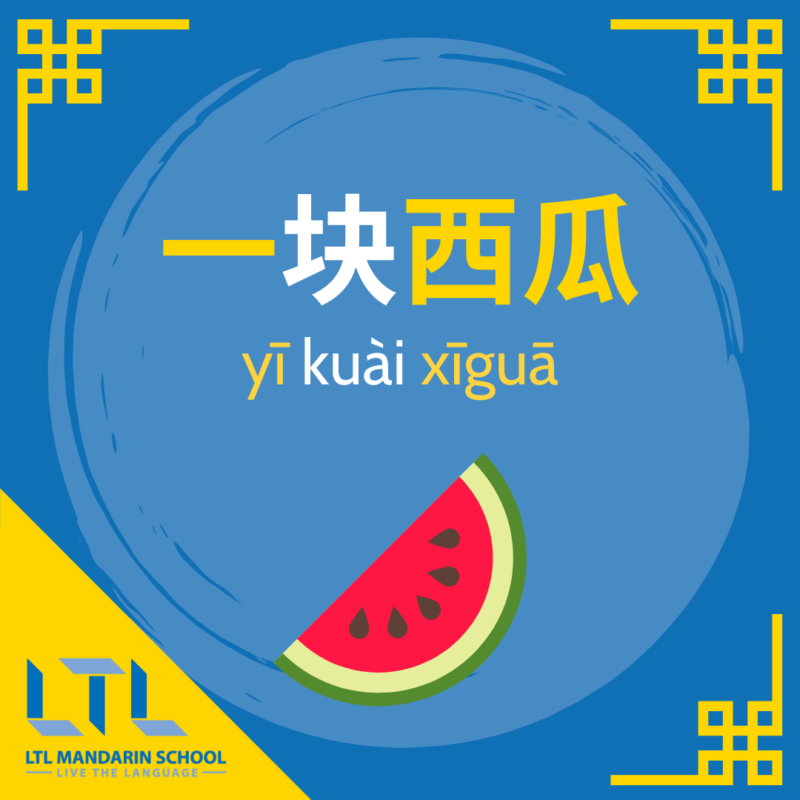

Chinese and Japanese Numbers || Counters and Measure Words

Chinese and Japanese Numbers || Lucky and Unlucky Numbers

Chinese and Japanese Numbers || Number Slang

Chinese and Japanese Numbers || FAQ’s

Chinese Numbers | The Ultimate Guide (PLUS Free Quiz Inside)

The Most Comprehensive Online Guide for Counting in Chinese & Talking About Numbers Chinese Numbers are one of the first things you’ll study when learning Chinese. So, we’ve prepared this ultimate guide to Mandarin Chinese numbers which covers numbers in…

Chinese and Japanese Numbers // Reading and Writing 1-10,000

You may expect Japanese and Chinese to use different writing systems for numbers – after all, they’re two very different languages, right?

You may be surprised to learn that Chinese and Japanese both use the same system for writing numbers.

This is because a large portion of the Japanese writing system is made up of Kanji, which are characters imported from Chinese.

In Chinese, these characters are called hanzi.

This shared system means if you can write numbers 1-10 in Chinese, you can do the same in Japanese!

Still skeptical? Let’s take a quick look at the hanzi and kanji used to write 1-10:

| Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Japanese Kanji | 一 | 二 | 三 | 四 | 五 | 六 | 七 | 八 | 九 | 十 |

| Chinese Hanzi | 一 | 二 | 三 | 四 | 五 | 六 | 七 | 八 | 九 | 十 |

Is the pronunciation the same?

No! 1-10 are pronounced differently in Chinese and Japanese.

One of the key reasons is that Chinese is a tonal language, meaning each word has to be said using one of the four tones.

You can also check out our ultimate guide to learning and remembering Chinese tones!

Slightly more confusingly, Japanese has two systems of reading numbers: kunyomi and onyomi.

Kunyomi originates from Japan, whereas onyomi has origins in Chinese, which is where Kanji comes from.

To keep things simple, here we’ve just included the Onyomi pronunciation, which you’ll usually learn first and use more often!

Let’s take a look at how Chinese and Japanese pronunciation compare:

| Number | Hanzi/Kanji | Chinese Pronunciation | Japanese Pronunciation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 一 | yī | ichi |

| 2 | 二 | èr | ni |

| 3 | 三 | sān | san |

| 4 | 四 | sì | shi / yon |

| 5 | 五 | wǔ | go |

| 6 | 六 | liù | roku |

| 7 | 七 | qī | shichi / nana |

| 8 | 八 | bā | hachi |

| 9 | 九 | jiǔ | kyuu / ku |

| 10 | 十 | shí | juu |

Did you know: If you can say 1-10 in Chinese and Japanese, you can already count to 99 in both languages!

That’s because Chinese and Japanese use the same straightforward counting system.

First, let’s take a look at 11-19. See if you can spot a pattern!

| Number | Hanzi/Kanji | Chinese Pronunciation | Japanese Pronunciation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | 十一 | shí yī | juu ichi |

| 12 | 十二 | shí èr | juu ni |

| 13 | 十三 | shí sān | juu san |

| 14 | 十四 | shí sì | juu shi / juu yon |

| 15 | 十五 | shí wǔ | juu go |

| 16 | 十六 | shí liù | juu roku |

| 17 | 十七 | shí qī | juu shichi / juu nana |

| 18 | 十八 | shí bā | juu hachi |

| 19 | 十九 | shí jiǔ | juu kyuu / juu ku |

🤳 FUN FACT If you’re learning numbers so you can give out your contact details, remember that Japanese people say Moshi Moshi when answering the phone!

You may have noticed, for both Japanese and Chinese, you simply need to say 10, followed by the number 1-9. Easy, right?

How about numbers 20-90? Just like last time, see if you can spot the pattern!

| Number | Hanzi/Kanji | Chinese Pronunciation | Japanese Pronunciation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 二十 | èr shí | ni juu |

| 30 | 三十 | sān shí | san juu |

| 40 | 四十 | sì shí | shi juu / yon juu |

| 50 | 五十 | wǔ shí | go juu |

| 60 | 六十 | liù shí | roku juu |

| 70 | 七十 | qī shí | shichi juu / nana juu |

| 80 | 八十 | bā shí | hachi juu |

| 90 | 九十 | jiǔ shí | kyuu juu |

Seeing a trend here?

For 20-90, you simply need to add the number 2-9 before 10. For example, thirty in both languages is “three ten” and fifty is “five-ten”. A lot more straightforward than English!

Before we show you 21-29, test your knowledge!

Using what you’ve just learned, can you guess which kanji/hanzi is used to write 21 in Japanese and Chinese?

- A)二十二

- B)十二一

- C)二十一

21 written in Chinese and Japanese is…

C) 二十一

That’s because 二 is two, 十 is ten and 一 is one. So 二十一 (‘two ten one‘) in both languages equals 21!

Let’s try a bigger number!

Can you guess which hanzi/kanji is used to write 99?

A)九十十

B)九十九

C)十九十

99 written in Chinese and Japanese is…

B) 九十九

That’s because 九 is nine, 十 is ten and 九 is nine. So 九十九 (‘nine ten nine‘) in both languages equals 99!

By now, you’re probably getting the hang of how numbers are written in Chinese and Japanese.

Just to help you really understand, here’s how to write 21-29 in both languages!

| Number | Hanzi/Kanji | Chinese Pronunciation | Japanese Pronunciation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21 | 二十一 | èr shí yī | ni juu ichi |

| 22 | 二十二 | èr shí èr | ni juu ni |

| 23 | 二十三 | èr shí sān | ni juu san |

| 24 | 二十四 | èr shí sì | ni juu shi / ni juu yon |

| 25 | 二十五 | èr shí wǔ | ni juu go |

| 26 | 二十六 | èr shí liù | ni juu roku |

| 27 | 二十七 | èr shí qī | ni juu shichi / ni juu nana |

| 28 | 二十八 | èr shí bā | ni juu hachi |

| 29 | 二十九 | èr shí jiǔ | ni juu kyuu / ni juu ku |

For every single number from 1-99, you can check out our Ultimate Japanese Number Guide or our Ultimate Chinese Number Guide!

Now, how about bigger numbers?

As with writing smaller numbers in Chinese and Japanese, the written characters for larger numbers are the same in both languages – but the pronunciation is different!

| Number | Hanzi/Kanji | Chinese Pronunciation | Japanese Pronunciation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 百 | bǎi | hyaku |

| 1000 | 千 | qiān | sen |

| 10,000 | 万 | wàn | man |

You may have noticed, 10,000 in Chinese and Japanese is not ‘ten thousands’, or ‘十千’. Instead, 10,000 has its own unit in kanji and hanzi: 万.

Did you know: Japanese and Chinese characters are written in a specific stroke order

If you’re feeling very ambitious, check out our crash course below for writing bigger numbers in Chinese, all the way up to one trillion!

Chinese and Japanese Numbers // How to Say the Date

How similar are the dates in Chinese and Japanese numbers?

Well actually, very, very similar!

In Japanese and Chinese, the date is written in order of biggest to smallest.

In other words, that means the year is written first, followed by the month and then the day.

Using numbers only, can you guess how would we would write the date for New Year’s Eve, 2022, in Japanese and Chinese?

2022/12/31

Remember, the year is written first (2022), then the month (12), then the day (31).

In both languages, we can also add the characters for year (年), month (月) and day (日), which would look like this: 2022年12月31日.

In English, months all have their own distinctive names and don’t follow a numerical system.

Whilst this can be a headache for English learners, Japanese and Chinese learners don’t have this problem at all!

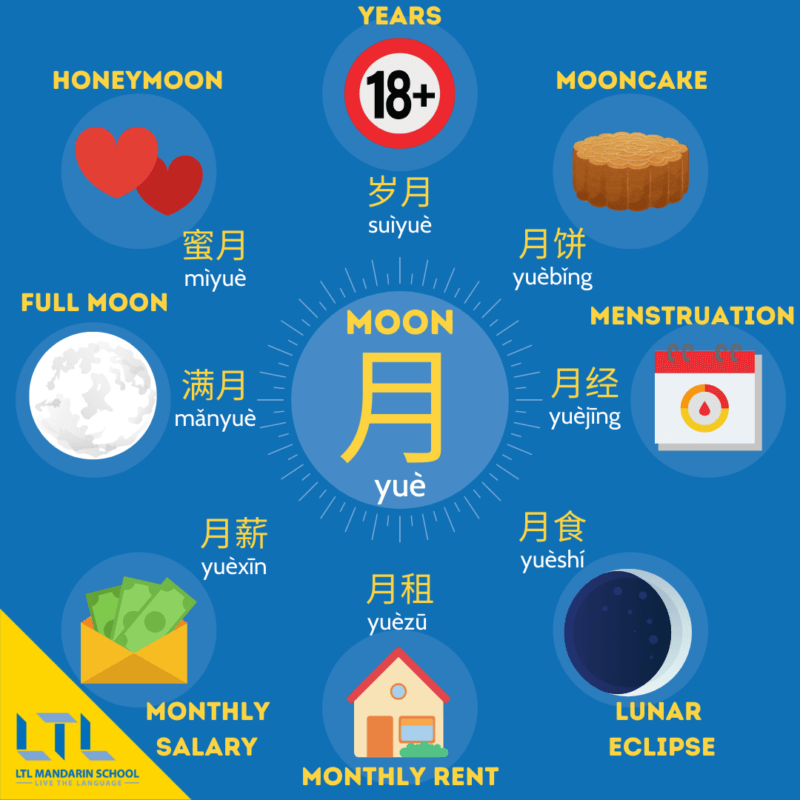

That’s because in both languages, there is special character used to write the word month: 月, which also means moon.

So conveniently, if you can read the months in one of the languages, you can recognize the word in both languages!

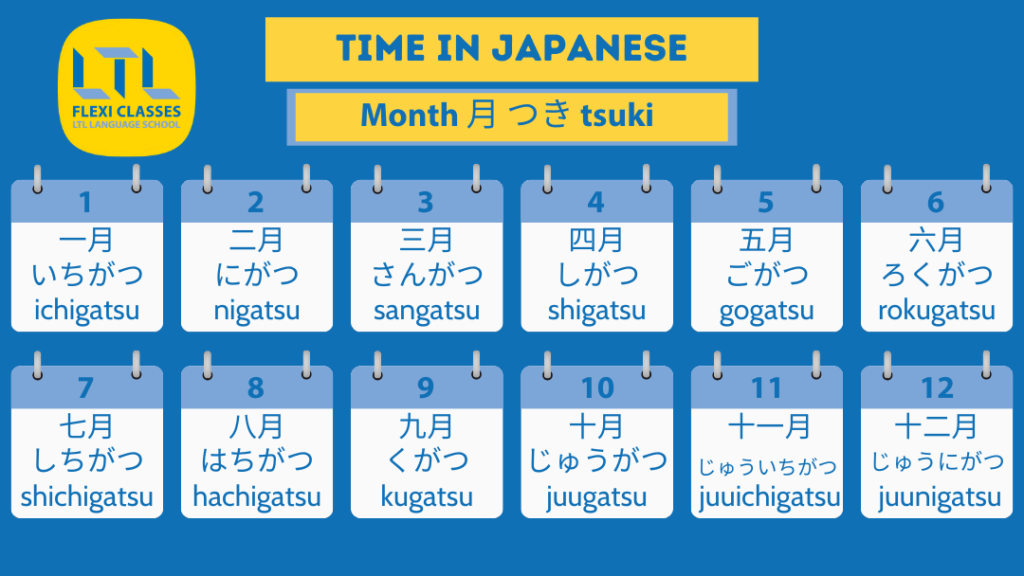

To write a specific month in either Chinese or Japanese, you simply write the character for 1-12 followed by 月.

For example, January is the first month, so we simple take the character for one (一) and add it before 月. In other words, January is 一月.

But don’t forget – the pronunciation of each of the months is very different in Chinese and Japanese!

| Month | Hanzi/Kanji | Chinese Pronunciation | Japanese Pronunciation |

|---|---|---|---|

| January | 一月 | yī yuè | ichi gatsu |

| February | 二月 | èr yuè | ni gatsu |

| March | 三月 | sān yuè | san gatsu |

| April | 四月 | sì yuè | shi gatsu |

| May | 五月 | wǔ yuè | go gatsu |

| June | 六月 | liù yuè | roku gatsu |

| July | 七月 | qī yuè | shichi gatsu |

| August | 八月 | bā yuè | hachi gatsu |

| September | 九月 | jiǔ yuè | ku gatsu |

| October | 十月 | shí yuè | juu gatsu |

| November | 十一月 | shíyī yuè | juuichi gatsu |

| December | 十二月 | shí’èr yuè | juuni gatsu |

Note: when writing the date in both languages, you can also make life easier and simply write the numerals 1-12 before 月, instead of using the hanzi and kanji!

2月 being February for example

Note: the word ‘month’ by itself is pronounced slightly differently (tsuki).

How about the date?

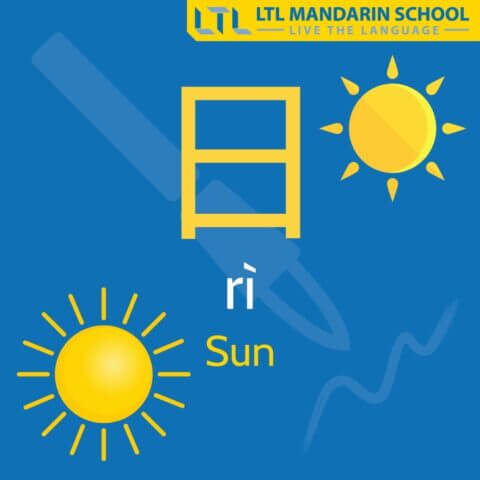

In both Chinese and Japanese, we can use the character for sun, 日 (in Chinese 日 is pronounced rì, in Japanese it is nichi) after a number to represent the day of the month.

However, the similarities stop there!

In Chinese, you also have the option of using the character 号 hào, which means number, instead of 日 rì.

Additionally, in Chinese the system is very regular, meaning you simply say a number and add 日 rì or 号 hào to express the date.

Meanwhile in Japanese, almost half of the days of the month are irregular, including the first ten days of the month!

This means that whilst the written system doesn’t change, the pronunciation does.

For example, when talking about the date in Japanese, 1日 is not pronounced ichi nichi (literally ‘one day’), it instead has a whole new pronunciation: tsuitachi.

Let’s take a look at how the days of the month in Chinese and Japanese compare in closer detail…

| Day of the month | Hanzi/Kanji | Chinese Pronunciation | Japanese Pronunciation (* = irregular) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 一日 | yī rì | tsuitachi* |

| 2nd | 二日 | èr rì | futsuka* |

| 3rd | 三日 | sān rì | mikka* |

| 4th | 四日 | sì rì | yokka* |

| 5th | 五日 | wǔ rì | itsuka* |

| 6th | 六日 | liù rì | muika* |

| 7th | 七日 | qī rì | nanoka* |

| 8th | 八日 | bā rì | youka* |

| 9th | 九日 | jiǔ rì | kokonoka* |

| 10th | 十日 | shí rì | tooka* |

| 11th | 十一日 | shíyī rì | juuichi nichi |

| 12th | 十二日 | shí’èr rì | juuni nichi |

| 13th | 十三日 | shísān rì | juusan nichi |

| 14th | 十四日 | shísì rì | juuyokka* |

| 15th | 十五日 | shíwǔ rì | juugo nichi |

| 16th | 十六日 | shíliù rì | juuroku nichi |

| 17th | 十七日 | shíqī rì | juushichi nichi |

| 18th | 十八日 | shíbā rì | juuhachi nichi |

| 19th | 十九日 | shíjiǔ rì | juuku nichi |

| 20th | 二十日 | èrshí rì | hatsuka* |

| 21st | 二十一日 | èrshíyī rì | nijuuichi nichi |

| 22nd | 二十二日 | èrshíèr rì | nijuuni nichi |

| 23rd | 二十三日 | èrshísān rì | nijuusan nichi |

| 24th | 二十四日 | èrshísì rì | nijuuyokka* |

| 25th | 二十五日 | èrshíwǔ rì | nijuugo nichi |

| 26th | 二十六日 | èrshíliù rì | nijuuroku nichi |

| 27th | 二十七日 | èrshíqī rì | nijuushichi nichi |

| 28th | 二十八日 | èrshíbā rì | nijuuhachi nichi |

| 29th | 二十九日 | èrshíjiǔ rì | nijuuku nichi |

| 30th | 三十日 | sānshí rì | sanjuu nichi |

| 31st | 三十一日 | sānshíyī rì | sanjuuyichi nichi |

Note: when writing the date in both languages, you can also make life easier and simply write the numerals 1-31 before 日, instead of using the hanzi and kanji!

Due to their regularity, Chinese days of the month can generally be learned a lot faster.

So whilst learning days of the month in Japanese is certainly a challenge, at least all of you Chinese learners out there can relax!

But don’t worry Japanese learners, here’s a breakdown of the days of the month in Japanese to help you practice.

And don’t forget, even though pronunciation can be tricky, if you can read the date in one language, you can still read it in the other!

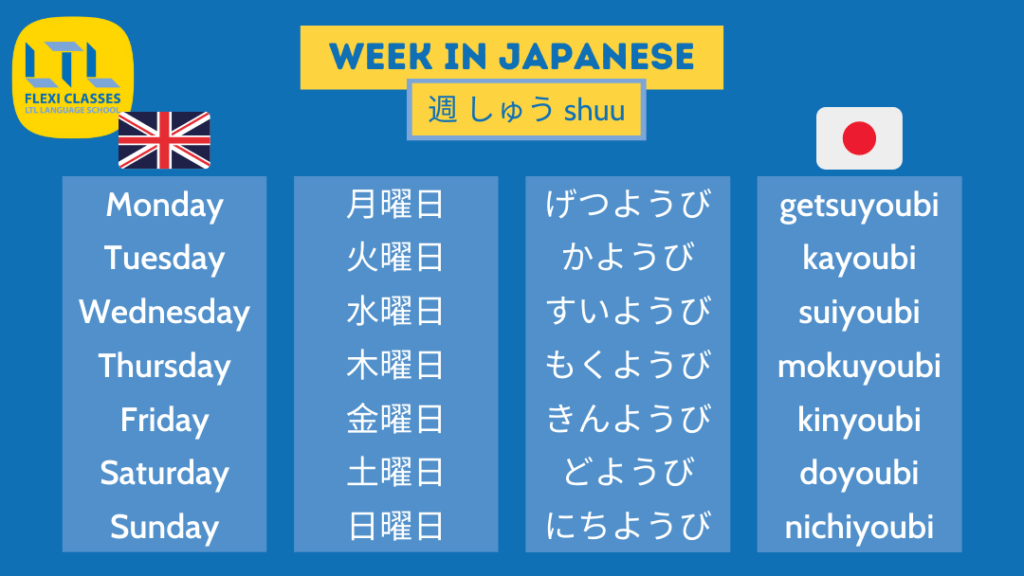

Meanwhile, days of the week are even less similar.

Chinese and Japanese use a different written system, so you’ll have to learn these separately!

Chinese is arguably a little easier here, as it follows a numerical system. You simply need to use the characters 星期 xīngqī and add a number to represent a day.

For example, in Chinese we can write Monday as 星期一 xīngqīyī, as 一 yī means one.

The only exception in Chinese is Sunday, which instead of a number, uses the character for sun: 日rì. This means Sunday is written as 星期日 xīngqīrì.

Alternatively, Sunday can also be written using the character 天 tiān, meaning day or sky. This gives us 星期天 xīngqītiān.

One the other hand, Japanese doesn’t use numbers to name the days of the week.

Instead, Japanese uses characters associated with different planets, the sun and the moon!

| Day of the Week | Chinese Hanzi and Pronunciation | Japanese Kanji and Pronunciation |

|---|---|---|

| Monday | 星期一 xīngqī yī | 月曜日 getsuyoubi |

| Tuesday | 星期二 xīngqī èr | 火曜日 kayoubi |

| Wednesday | 星期三 xīngqī sān | 水曜日 suiyoubi |

| Thursday | 星期四 xīngqī sì | 木曜日 mokuyoubi |

| Friday | 星期五 xīngqī wǔ | 金曜日 kinyoubi |

| Saturday | 星期六 xīngqī liù | 土曜日 doyoubi |

| Sunday | 星期日 xīngqī rì | 日曜日 nichiyoubi |

Chinese and Japanese Numbers // Ages

Ages are expressed in Chinese and Japanese using a number followed by a character to express ‘years old’.

The Chinese hanzi and Japanese kanji are actually of the same origin. The only difference is that mainland China uses the simplified character, whereas Japanese uses the traditional character.

In Japanese, ‘years old’ can be expressed with the kanji ~歳 (~sai)

In Chinese, ‘years old’ is most commonly written using the simplified version of the same character, ~岁 (~suì)

Note: In Taiwan, Hong Kong and Macau, traditional characters are still used!

However, when we put ‘years old’ into a full sentence, Japanese and Chinese start to look very different!

Take our quick quiz to see how much you remember so far!

True or False: Japan uses simplified characters, mainland China uses traditional characters

False!

Japan uses traditional characters, whereas mainland China uses simplified.

True or False: Chinese uses numbers to name the days of the week, Japanese does not

True!

Chinese adds a number to 星期 xīngqī to represent the day, e.g. 星期一 xīngqī yī is Monday because 一 yī means one. Meanwhile, Japan uses names that originate from the solar system.

True or False: 歳 is the character used for ‘years old’ in China

False! 歳 sai is Japanese kanji. Chinese uses the hanzi 岁 suì to represent ‘years old’.

Chinese and Japanese Numbers // Counters and Measure Words

WARNING: Complicated content ahead!

When counting almost anything in Chinese and Japanese, you need to add something called a measure word (Chinese) or counter (Japanese).

For many students, counters and measure words are one of the most confusing parts about learning Chinese and Japanese!

Different objects such as stationary, animals, clothes, food and people all have their own measure words and counters in Chinese and Japanese.

So what exactly are measure words and counters?

You might be surprised to learn that English has a similar concept when counting certain items.

Let’s take a look at an example sentence, see if you can spot the measure word:

I want to eat a slice of bread.

Found it? Here, ‘slice’ acts as a measure word, as it would be pretty weird to say ‘a bread’!

Other examples in English could be a drop, a piece, a roll of, a bottle of, a bowl of, etc.

The only difference in Japanese and Chinese is that almost every single object (unfortunately for learners!) is paired with a specific measure word or counter.

Even more unfortunately, there isn’t an awful lot lot of crossover in Japanese and Chinese measure words.

Let’s take a look at some common Chinese measure words:

In the above pictures, we can see coffee, tables and presents each have their own measure words.

Some are easier than others, for example 一杯咖啡 yībēi kāfēi translates directly to ‘a cup of coffee’, with the measure word 杯 bēi meaning ‘cup’.

On the other hand, 张 zhāng, the measure word for tables, and 件 jiàn, the measure word for presents, have no direct translation (we know, it’s tough at first!)

Luckily in both Chinese and Japanese, there are patterns in each language the use of measure words and counters.

For a more detailed look, take a peak at our Chinese Measure Word Guide and our Japanese Counters Guide.

There are hundreds of measure words and counters in Chinese and Japanese.

But don’t worry!

Luckily each language has a generic measure word that can be applied to almost anything.

Disclaimer: whilst it’s understandable to native speakers if you use the following generic measure word and counter in most situations, they’re not always 100% accurate so don’t slack on your measure word and counter study guys!

In Chinese, the most helpful of all measure words is the character 个 gè.

Neatly illustrated by Drake in this meme…

Simply add a number before 个 gè and you can pretty much count most objects. For example, 一个 yīgè is one of something, 十个 shígè is 10 of something.

In Japanese, the most generic counter with the widest usage is つ tsu

Similarly to Chinese, in written Japanese, you simply need to add a number before つ tsu to indicate how many of something is being counted.

So whilst the characters are different in Chinese and Japanese, the system is essentially the same.

However, as has been the general theme with some other Japanese counting systems, the reading of numbers with つ tsu is almost entirely irregular.

Let’s take a look at how you could count things using the most generic measure word in Chinese (个 gè) and the most common counter in Japanese (つ tsu).

| Number of objects (generic) | Chinese Measure Word and Pronunciation (* = irregular) | Japanese Counter and Pronunciation (* = irregular) |

|---|---|---|

| one | 一个 yī gè | 一つ hitotsu* |

| two | 两个 liǎng gè* | 二つ futatsu* |

| three | 三个 sān gè | 三つ mittsu* |

| four | 四个 sì gè | 四つ yottsu* |

| five | 五个 wǔ gè | 五つ itsutsu* |

| six | 六个 liù gè | 六つ yottsu* |

| seven | 七个 qī gè | 七つ nanatsu |

| eight | 八个 bā gè | 八つ yatsu* |

| nine | 九个 jiǔ gè | 九つ kokonotsu* |

| ten | 十个 shí gè | 十つ toou* |

In a nutshell, Chinese and Japanese both use a complex measure word system, which for learners usually presents a bit of a headache!

However, even though the measure word applications and characters differ in each language, learning either Chinese or Japanese will still give you a head-start in learning the other, as you’ll already have grasped this tricky topic!

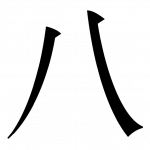

Chinese and Japanese Numbers // Lucky and Unlucky Numbers

Lucky Numbers

Any guesses as to why the Beijing Olympics Games started at exactly 8 minutes and 8 seconds past 8pm on 08/08/2008?

That’s right – 8 is a very, very lucky number in Chinese!

That’s because the pronunciation of the number 8, bā, sound similar to that of the character 发 fā, which means wealthy or becoming prosperous.

The number 8 in China is so lucky in fact, houses or apartments that end in the number 8 are more expensive!

Whilst not as popular as it is in China, the number 8 is also relatively lucky in Japan. That’s because in Japan, 8 also has links to prosperity and wealth.

However, that’s not because of the pronunciation of 8, it’s actually due to the shape of the character 八! This kanji widens at the bottom, symbolising growth.

The luckiest number in Japan, similar to many western countries, is number 7!

7, pronounced nana or shichi, has strong links to Buddhism, one of the most common religions in Japan.

Buddhists celebrate a baby’s birth after seven days and mourn a life seven days after death.

There are even seven lucky gods 七福神 ingrained deeply in Japanese culture and a star festival, Tanabata, that is celebrated on 7/7 every year.

To learn more about how numbers are viewed in China, check out our full guide to lucky numbers in Chinese!

Unlucky Numbers

In both Japanese and Chinese, there is a number that is the most feared of all…

Number 4!

This number is associated with perhaps the worst thing of all (except taxes) death.

Both the Chinese pronunciation sì and the Japanese pronunciation shi sound like the word for death.

In both languages, the character for death is 死. In Chinese this is pronounced sǐ and in Japanese it is pronounced shi.

This number is so widely feared, that often in Chinese and Japanese buildings the fourth floor will be totally missing.

So next time you’re in an elevator in either of these countries, take a look to see if there’s a number 4 button!

Chinese and Japanese Numbers // Number Slang

11/11 is the biggest shopping day on the planet.

It’s known as Single’s Day and it’s celebrated in China and Japan. Can you guess why it’s celebrated on November 11th?

Because of course, all the 1s!

Chinese and Japanese are both exceptionally creative with numbers as both languages have many, many homophones (words that sound the same with different meanings).

As homophones and slang are pretty specific to a language, there’s not a lot of crossover between Chinese and Japanese.

But here’s three of our favorites from each language!

Chinese Number Slang

- 520 = I love you. 5 wǔ 2 èr 0 líng sounds very much like 我爱你 wǒ ài nǐ. This slang has become so popular that May 20th (5/20) has even become a new form of Valentine’s Day!

- 88 = bye bye. Bye bye is also commonly used in Chinese, but it also sounds like two number 8s: bābā!

- 514 = I want to die. This one is a little bit dramatic, but is often used to exaggerate in mildly disappointing situations! 514 is pronounced wǔyīsì, which sounds like I want to die 我要死 wǒyàosǐ.

Japanese Number Slang

- 888 = hahaha. The kanji for 八 looks identical to the Japanese katakana (another alphabet used in Japanese) character 八, which is pronounced ha. Therefore, 八八八 would sound like hahaha!

- 555 = go go go! In Japanese, 5 is pronounced as go, so this one is also a play on English. This one is a favourite of online gamers, particularly before going into battle!

- 39 = thank you. This number slang is another play on English. 3 in Japanese is pronounced san and 9 is kyuu, so together sankyuu sounds like a very cute thank you!

FAQs

How do I count to 10 in Chinese?

1 一 yī

2 二 èr

3 三 sān

4 四 sì

5 五 wǔ

6 六 liù

7 七 qī

8 八 bā

9 九 jiǔ

10 十 shí

How do I count to 10 in Japanese?

1 一 ichi

2 二 ni

3 三 san

4 四 yon / shi

5 五 go

6 六 roku

7 七 nana / shichi

8 八 hachi

9 九 kyuu / ku

10 十 juu

Are numbers the same in Chinese and Japanese?

Yes and no!

The written characters for each number in Japanese and Chinese is the same, as the Japanese kanji originates from Chinese hanzi.

However, the pronunciation is very different.

What are measure words and counters?

Measure words (Chinese) and counters (Japanese) are used before nouns. There are different measure words and counters for different types of objects.

Similar equivalents in English include ‘a glass of’, ‘a piece of’ or ‘a slice of’.

Is it easier to learn to count in Japanese or Chinese?

When learning numbers 1-1000 (and above!) in either language, counting systems are actually very similar.

Initially Chinese may be harder for native English speakers, as the language uses tones.

However, when it comes to saying dates, days and counting objects, Japanese is a little harder as a lot more of the language is irregular and doesn’t follow a numerical pattern like Chinese.

Where can I get online Japanese lessons?

Take a look at our online Japanese Flexi Classes!

Where can I get online Chinese lessons?

Take a look at our online Chinese Flexi Classes!

Want more from LTL?

If you wish to hear more from LTL Language School why not join our mailing list.

We give plenty of handy information on learning Chinese, useful apps to learn the language and everything going on at our LTL schools!

Sign up below and become part of our ever growing community!

BONUS | Want to study the local Taiwanese dialect known as Hokkien? We provide Hokkien classes in person and online.

Hi, my name is Greta. I am from Italy and I work as a student advisor at our Taipei school.

Hi, my name is Greta. I am from Italy and I work as a student advisor at our Taipei school. Hi, my name is Manuel! I am from Spain and I am a Student Advisor at LTL. I’m now based at our Seoul School after living 3 years in Taipei.

Hi, my name is Manuel! I am from Spain and I am a Student Advisor at LTL. I’m now based at our Seoul School after living 3 years in Taipei.